Original release date: May 5, 2020

Summary

This is a joint alert from the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).

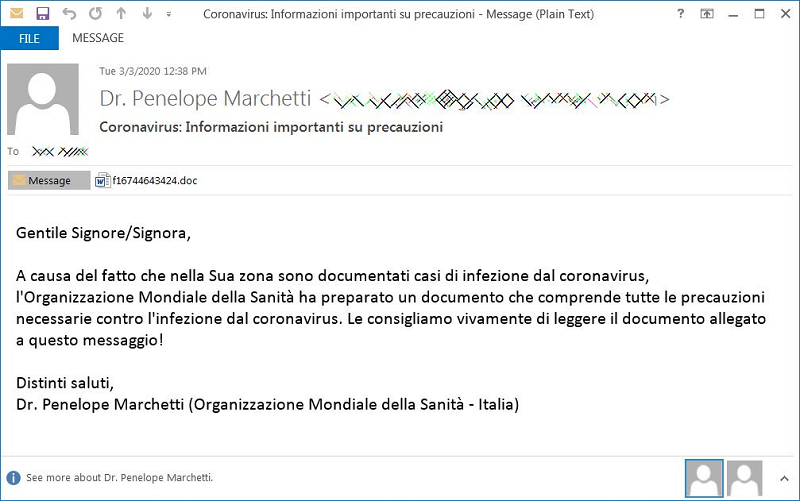

CISA and NCSC continue to see indications that advanced persistent threat (APT) groups are exploiting the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic as part of their cyber operations. This joint alert highlights ongoing activity by APT groups against organizations involved in both national and international COVID-19 responses. It describes some of the methods these actors are using to target organizations and provides mitigation advice.

The joint CISA-NCSC Alert: (AA20-099A) COVID-19 Exploited by Malicious Cyber Actors from April 8, 2020, previously detailed the exploitation of the COVID-19 pandemic by cybercriminals and APT groups. This joint CISA-NCSC Alert provides an update to ongoing malicious cyber activity relating to COVID-19. For a graphical summary of CISA’s joint COVID-19 Alerts with NCSC, see the following guide.

COVID-19-related targeting

APT actors are actively targeting organizations involved in both national and international COVID-19 responses. These organizations include healthcare bodies, pharmaceutical companies, academia, medical research organizations, and local governments.

APT actors frequently target organizations in order to collect bulk personal information, intellectual property, and intelligence that aligns with national priorities.

The pandemic has likely raised additional interest for APT actors to gather information related to COVID-19. For example, actors may seek to obtain intelligence on national and international healthcare policy, or acquire sensitive data on COVID-19-related research.

Targeting of pharmaceutical and research organizations

CISA and NCSC are currently investigating a number of incidents in which threat actors are targeting pharmaceutical companies, medical research organizations, and universities. APT groups frequently target such organizations in order to steal sensitive research data and intellectual property for commercial and state benefit. Organizations involved in COVID-19-related research are attractive targets for APT actors looking to obtain information for their domestic research efforts into COVID-19-related medicine.

These organizations’ global reach and international supply chains increase exposure to malicious cyber actors. Actors view supply chains as a weak link that they can exploit to obtain access to better-protected targets. Many supply chain elements have also been affected by the shift to remote working and the new vulnerabilities that have resulted.

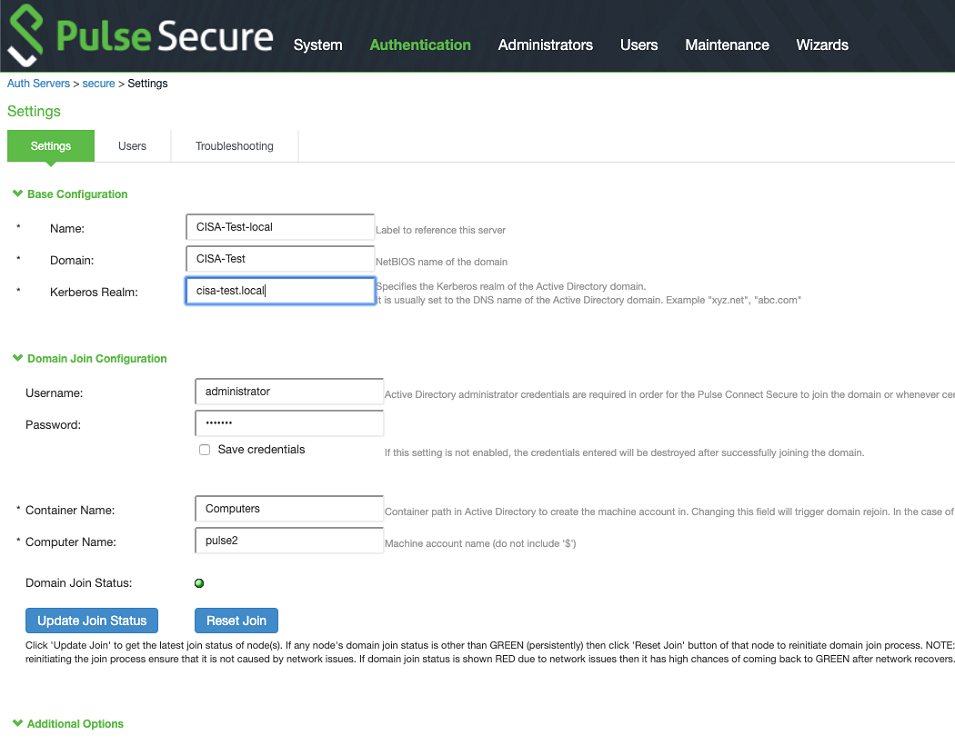

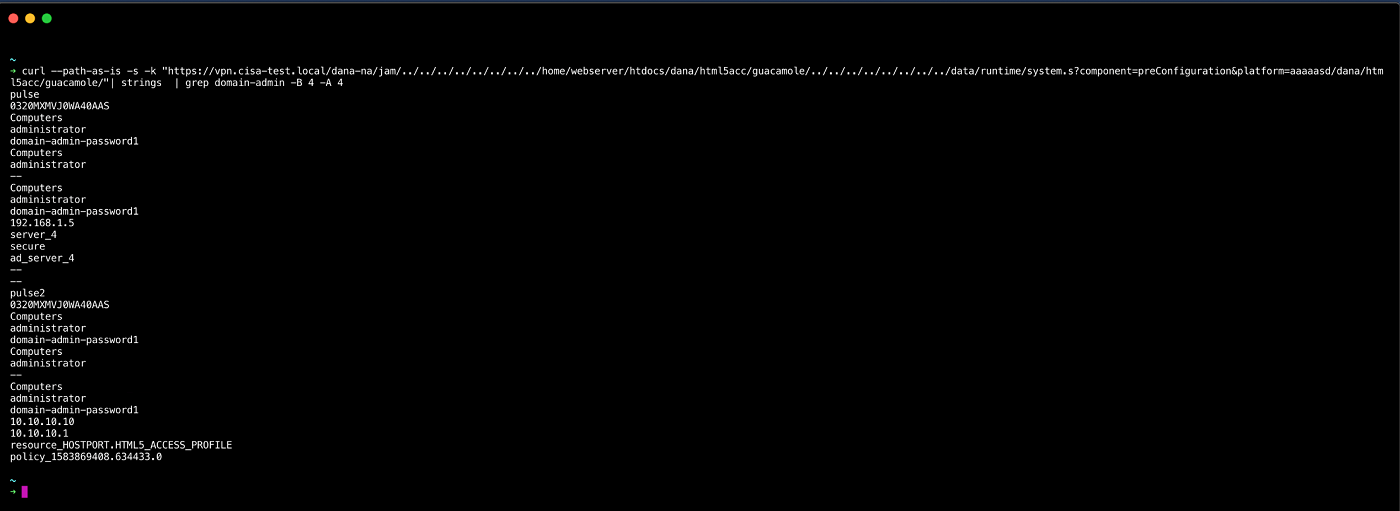

Recently CISA and NCSC have seen APT actors scanning the external websites of targeted companies and looking for vulnerabilities in unpatched software. Actors are known to take advantage of Citrix vulnerability CVE-2019-19781[1],[2] and vulnerabilities in virtual private network (VPN) products from Pulse Secure, Fortinet, and Palo Alto.[3],[4]

COVID-19-related password spraying activity

CISA and NCSC are actively investigating large-scale password spraying campaigns conducted by APT groups. These actors are using this type of attack to target healthcare entities in a number of countries—including the United Kingdom and the United States—as well as international healthcare organizations.

Previously, APT groups have used password spraying to target a range of organizations and companies across sectors—including government, emergency services, law enforcement, academia and research organizations, financial institutions, and telecommunications and retail companies.

Technical Details

Password spraying is a commonly used style of brute force attack in which the attacker tries a single and commonly used password against many accounts before moving on to try a second password, and so on. This technique allows the attacker to remain undetected by avoiding rapid or frequent account lockouts. These attacks are successful because, for any given large set of users, there will likely be some with common passwords.

Malicious cyber actors, including APT groups, collate names from various online sources that provide organizational details and use this information to identify possible accounts for targeted institutions. The actors will then “spray” the identified accounts with lists of commonly used passwords.

Once the malicious cyber actor compromises a single account, they will use it to access other accounts where the credentials are reused. Additionally, the actor could attempt to move laterally across the network to steal additional data and implement further attacks against other accounts within the network.

In previous incidents investigated by CISA and NCSC, malicious cyber actors used password spraying to compromise email accounts in an organization and then, in turn, used these accounts to download the victim organization’s Global Address List (GAL). The actors then used the GAL to password spray further accounts.

NCSC has previously provided examples of frequently found passwords, which attackers are known to use in password spray attacks to attempt to gain access to corporate accounts and networks. In these attacks, malicious cyber actors often use passwords based on the month of the year, seasons, and the name of the company or organization.

CISA and NCSC continue to investigate activity linked to large-scale password spraying campaigns. APT actors will continue to exploit COVID-19 as they seek to answer additional intelligence questions relating to the pandemic. CISA and NCSC advise organizations to follow the mitigation advice below in view of this heightened activity.

Mitigations

CISA and NCSC have previously published information for organizations on password spraying and improving password policy. Putting this into practice will significantly reduce the chance of compromise from this kind of attack.

- CISA alert on password spraying attacks

- CISA guidance on choosing and protecting passwords

- CISA guidance on supplementing passwords

- NCSC guidance on password spraying attacks

- NCSC guidance on password administration for system owners

- NCSC guidance on password deny lists

CISA’s Cyber Essentials for small organizations provides guiding principles for leaders to develop a culture of security and specific actions for IT professionals to put that culture into action. Additionally, the UK government’s Cyber Aware campaign provides useful advice for individuals on how to stay secure online during the coronavirus pandemic. This includes advice on protecting passwords, accounts, and devices.

A number of other mitigations will be of use in defending against the campaigns detailed in this report:

- Update VPNs, network infrastructure devices, and devices being used to remote into work environments with the latest software patches and configurations. See CISA’s guidance on enterprise VPN security and NCSC guidance on virtual private networks for more information.

- Use multi-factor authentication to reduce the impact of password compromises. See the U.S. National Cybersecurity Awareness Month’s how-to guide for multi-factor authentication. Also see NCSC guidance on multi-factor authentication services and setting up two factor authentication.

- Protect the management interfaces of your critical operational systems. In particular, use browse-down architecture to prevent attackers easily gaining privileged access to your most vital assets. See the NCSC blog on protecting management interfaces.

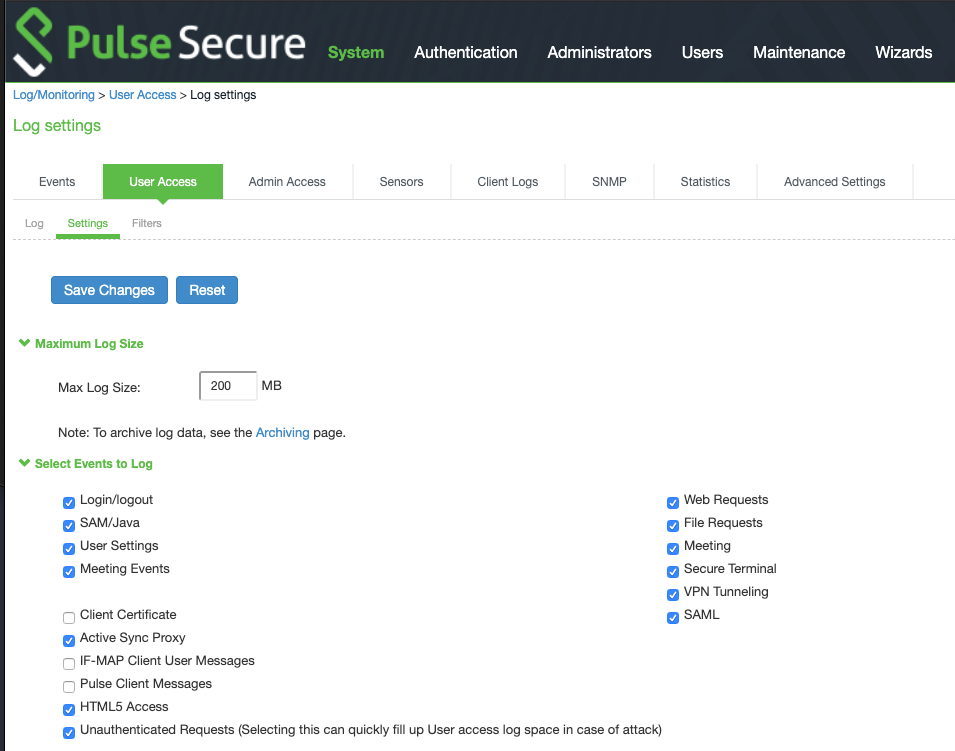

- Set up a security monitoring capability so you are collecting the data that will be needed to analyze network intrusions. See the NCSC introduction to logging security purposes.

- Review and refresh your incident management processes. See the NCSC guidance on incident management.

- Use modern systems and software. These have better security built in. If you cannot move off out-of-date platforms and applications straight away, there are short-term steps you can take to improve your position. See the NCSC guidance on obsolete platform security.

- Further information: Invest in preventing malware-based attacks across various scenarios. See CISA’s guidance on ransomware and protecting against malicious code. Also see the NCSC guidance on mitigating malware and ransomware attacks.

Contact Information

CISA encourages U.S. users and organizations to contribute any additional information that may relate to this threat by emailing CISAServiceDesk@cisa.dhs.gov.

The NCSC encourages UK organizations to report any suspicious activity to the NCSC via their website: https://report.ncsc.gov.uk/.

Disclaimers

This report draws on information derived from CISA, NCSC, and industry sources. Any findings and recommendations made have not been provided with the intention of avoiding all risks and following the recommendations will not remove all such risk. Ownership of information risks remains with the relevant system owner at all times.

CISA does not endorse any commercial product or service, including any subjects of analysis. Any reference to specific commercial products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply their endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by CISA.

References

- [1] CISA Alert: Detecting Citrix CVE-2019-19781

- [2] NCSC Alert: Actors exploiting Citrix products vulnerability

- [3] CISA Alert: Continued Exploitation of Pulse Secure VPN Vulnerability

- [4] NCSC Alert: Vulnerabilities exploited in VPN products used worldwide

Revisions

- May 5, 2020: Initial Version

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.