Asset management and website performance optimization are two of those unavoidable headaches faced by every website owner.

Asset management and website performance optimization are two of those unavoidable headaches faced by every website owner.

A digital asset management (DAM) platform can provide centralized asset repositories with intuitive dashboards to help you manage assets. On the other hand, an image CDN can help you get rid of that messy responsive syntax and provide dynamic asset optimization with huge performance boosts.

The problem is that website performance has become such a competitive factor that DAMs with other priorities tend to fall short. On the other hand, specialized image CDNs don’t solve the problems associated with image management, particularly within organizations.

With that in mind, I propose solving these problems for good by putting together image management and optimization stack using ImageEngine and Cloudinary. Instead of being a comparison between these two tools, this article describes the benefits of using them to complement each other.

Features and Asset Management Capabilities

As a DAM, Cloudinary provides you with a visual interface to store, manage, and edit your image and video assets. In that way, it’s not much different from any other professional image managing software such as Adobe Bridge, except that it’s an online, browser-based service.

Using the Media Library, you can upload, delete, and organize images in folders, for example. The visual image editor allows you to make advanced transformations and image touch-ups and see the results instantaneously using tools like sliders, dropdowns, etc. You can even chain transformations together for multi-layered effects.

Cloudinary also allows you to manipulate images and videos this way using their URL-based API.

Cloudinary has additional auxiliary features that make asset management easier (especially in organizations), such as backups, role-based multi-user admin, and feature extensions via third-party integrations and add-ons.

This is something most image CDNs don’t provide. Instead, they allow you to access and transform images using URL manipulation. Transformations are usually made using string-based parameters or directives. A serverless, headless DAM, if you will.

However, the advantage of using a dedicated image CDN like ImageEngine, is that it can usually provide enhanced asset optimization. ImageEngine, for example, is an intelligent image CDN that uses WURFL device detection to finely read the context an image is accessed from (device model, PPI, OS, browser, resolution, etc.) and then chooses the optimal image for that configuration.

This frees up website owners from having to do any additional optimization. This business logic is also built-in to all of their global PoP servers, and ImageEngine specifically delivers cache-hit ratios close to 100%. The following performance section will illustrate the difference this can make in practice.

Check out the key differences between ImageEngine and Cloudinary. And, for a deeper insight, see the comparison with other similar CDNs, like imgix and Cloudflare

Performance

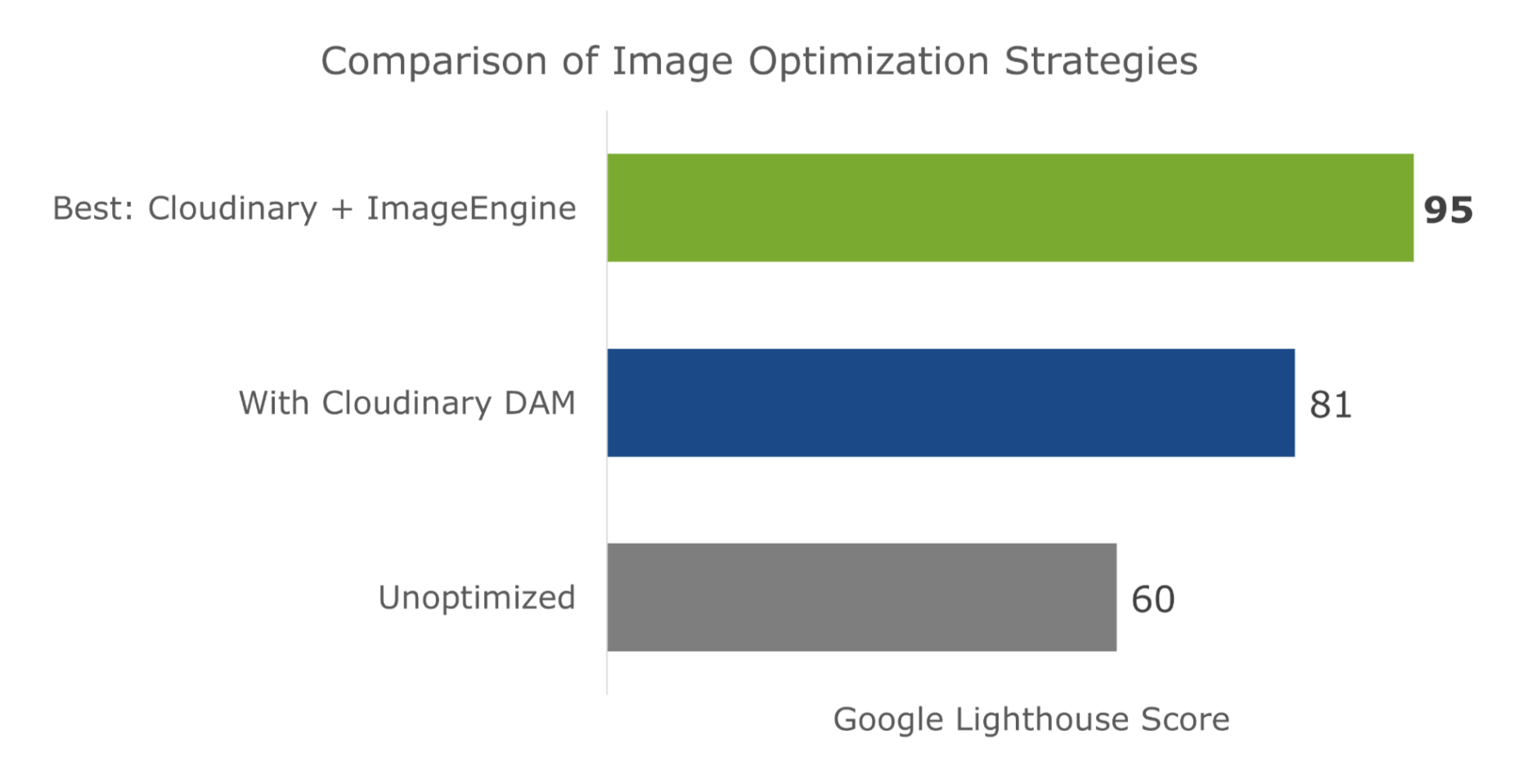

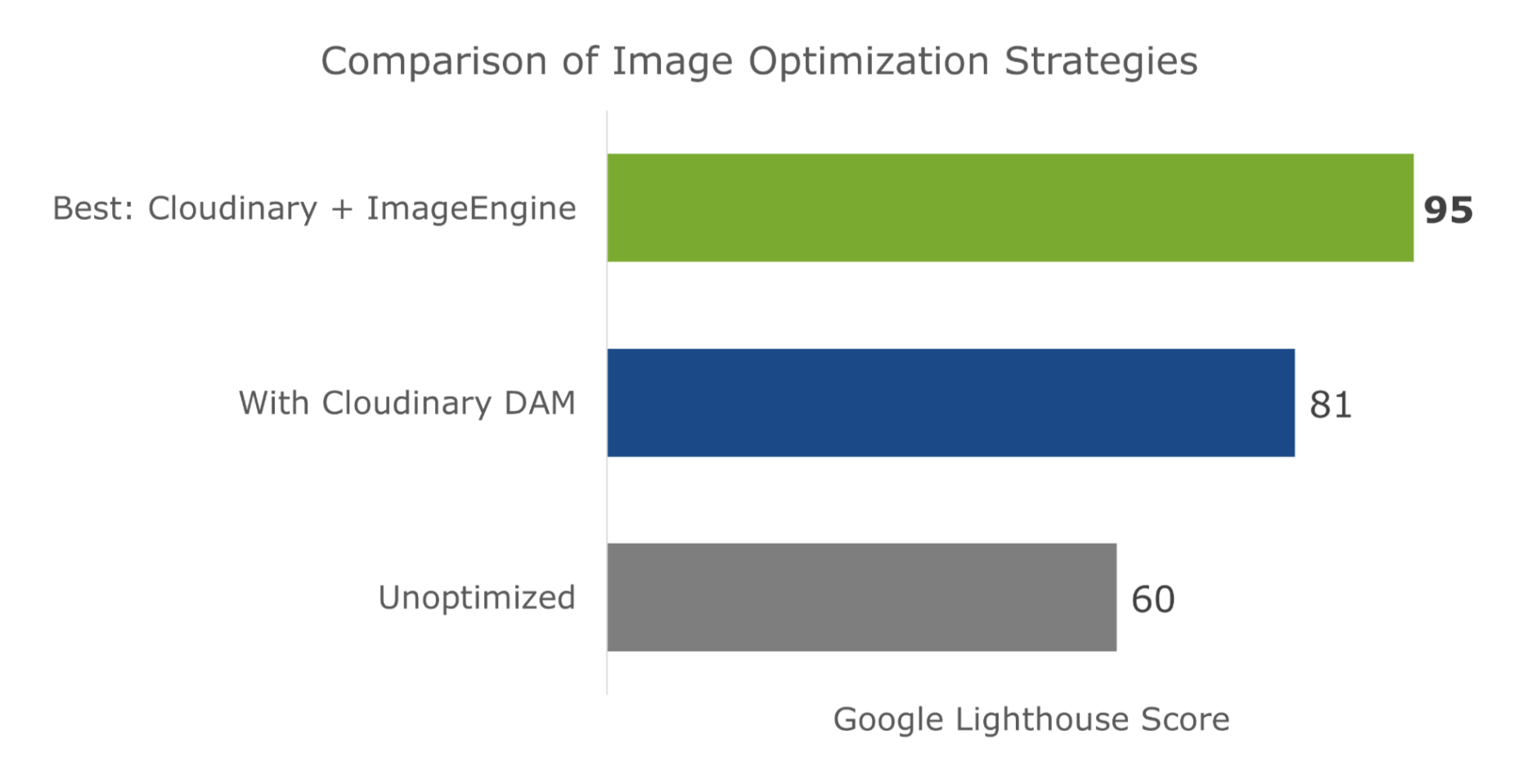

Just to cover our bases and prove that this is an effective asset management and optimization stack, I’m also going to affirm it using a Lighthouse performance audit. Here is a quick summary of the results:

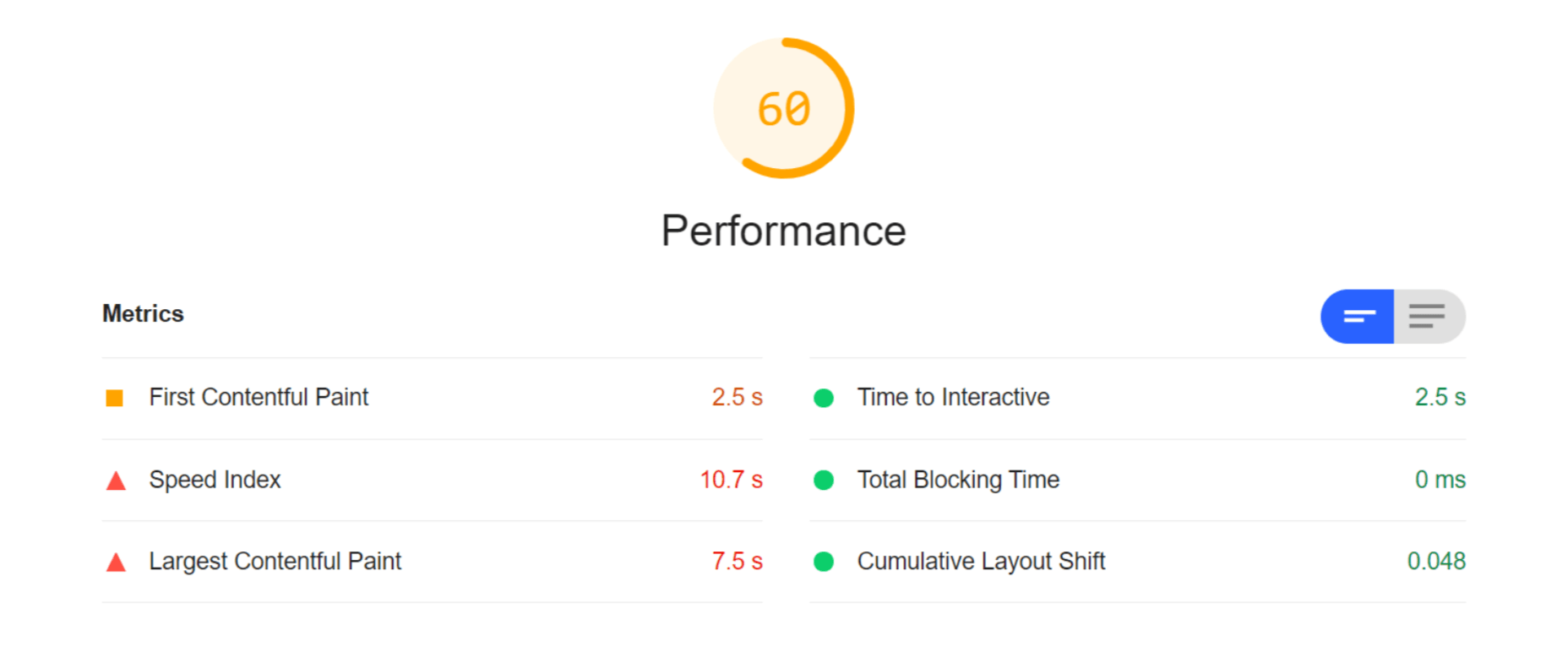

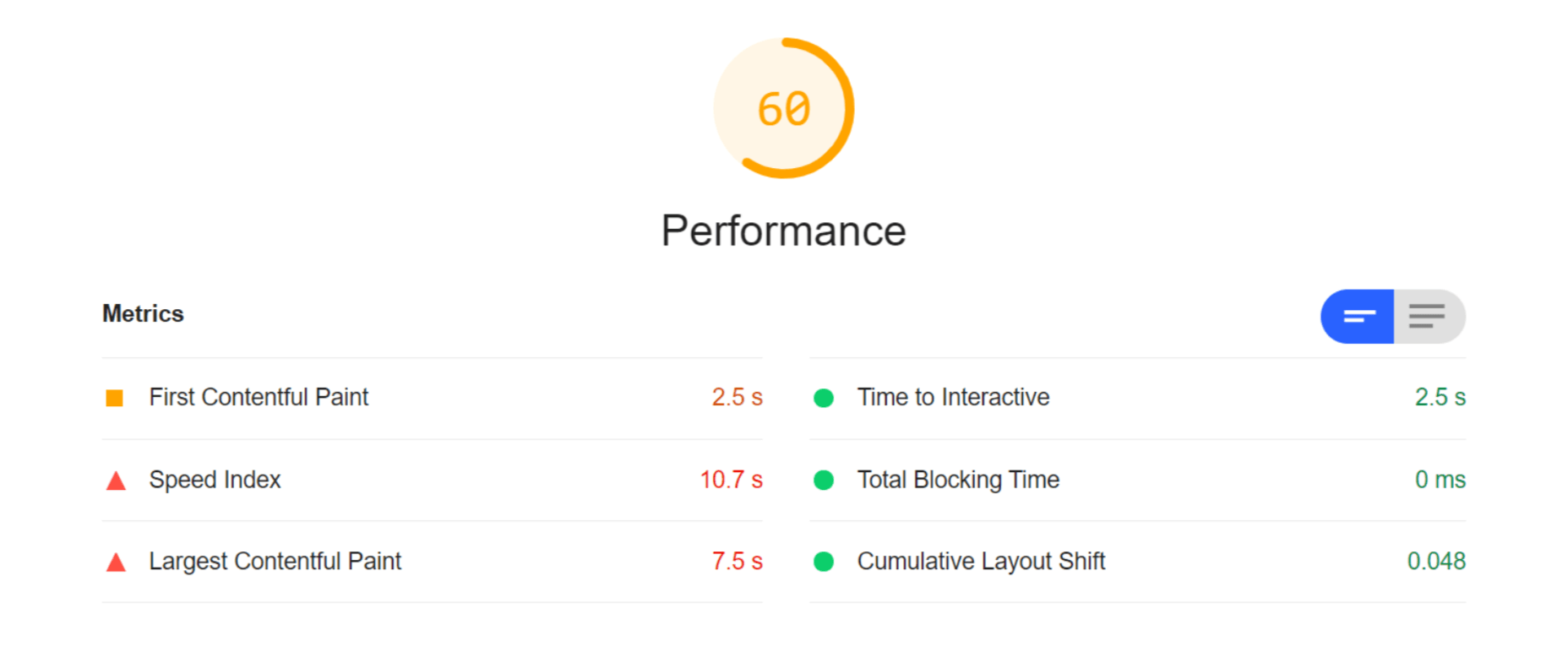

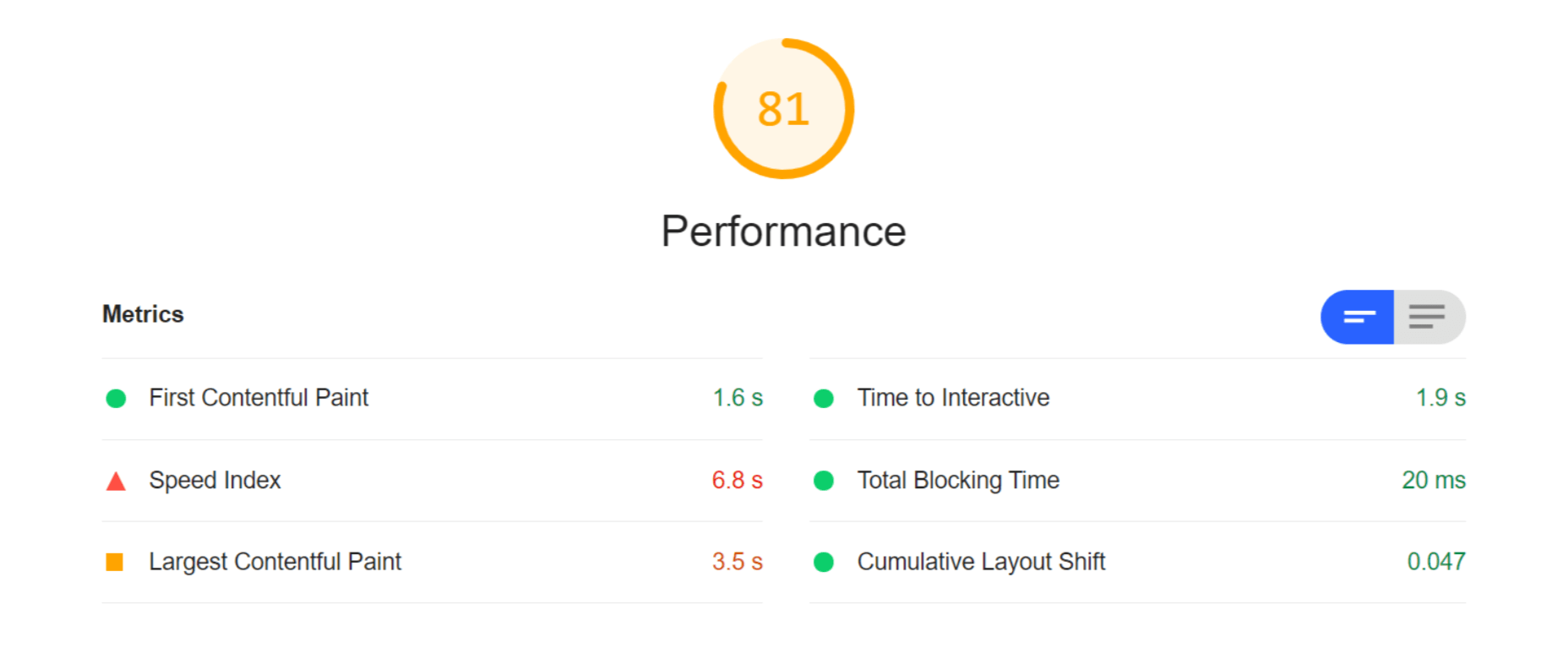

For this test, I built a web page with a tonne of images with overly large file sizes. In this first Lighthouse audit, I didn’t apply any optimization to the images. Here’s the result:

As you can see, we had some major problems when it came to the loading time of our assets. Overall, the page took more than 10 seconds to load. One of Google’s crucial user-centric performance metrics, LCP, scored a miserable 7.5s. Lighthouse suggested that some of the main problems encountered were the asset file size, inefficient cache policies, using non-optimal image formats, and improperly sized images.

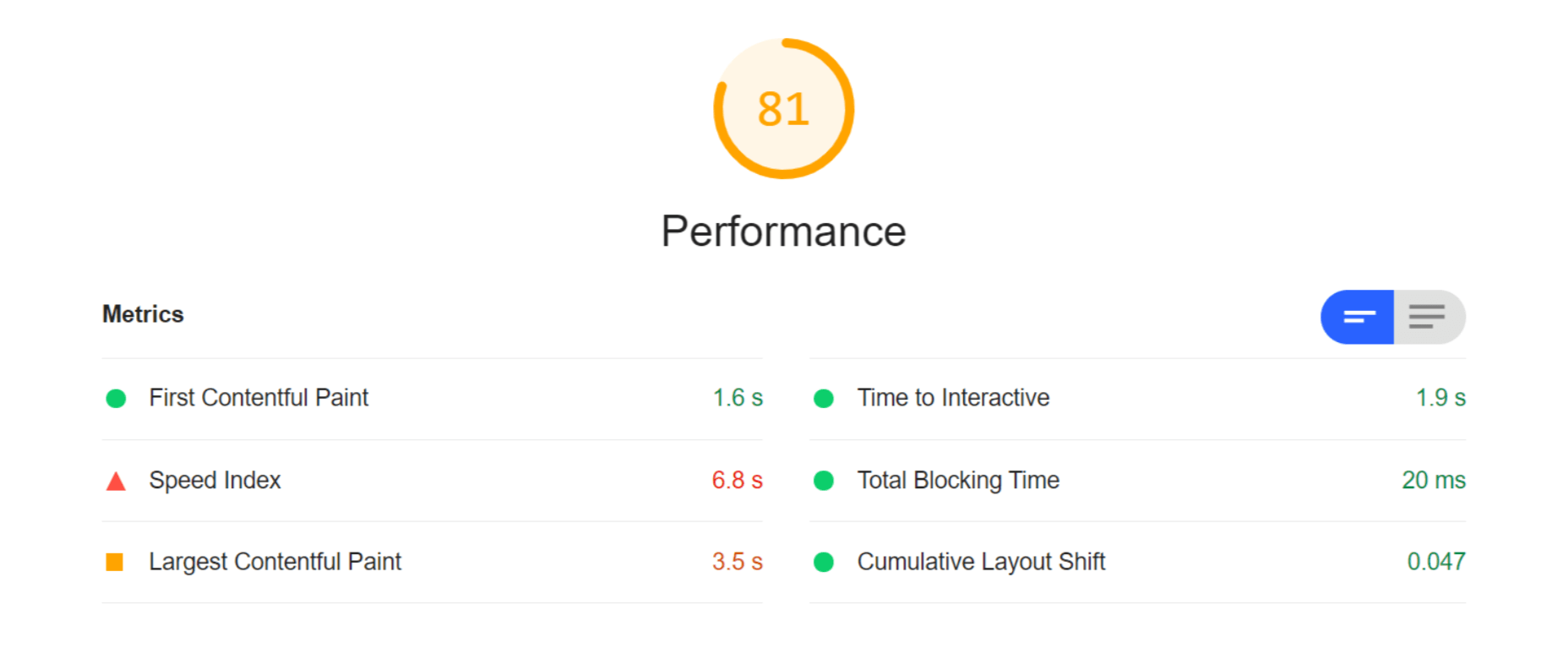

Both Cloudinary and ImageEngine are supposed to address all of these factors with their auto image optimization. In the next audit, I used the same page and content but served my images via Cloudinary:

As you can see, there is improvement in most factors. FCP is now in the green, and both the Speed index and LCP times have almost halved. Even TTI and CLS improved slightly. That being said, it’s still nowhere near optimal, and we’re still falling short of the all-important 3-second loading time ceiling.

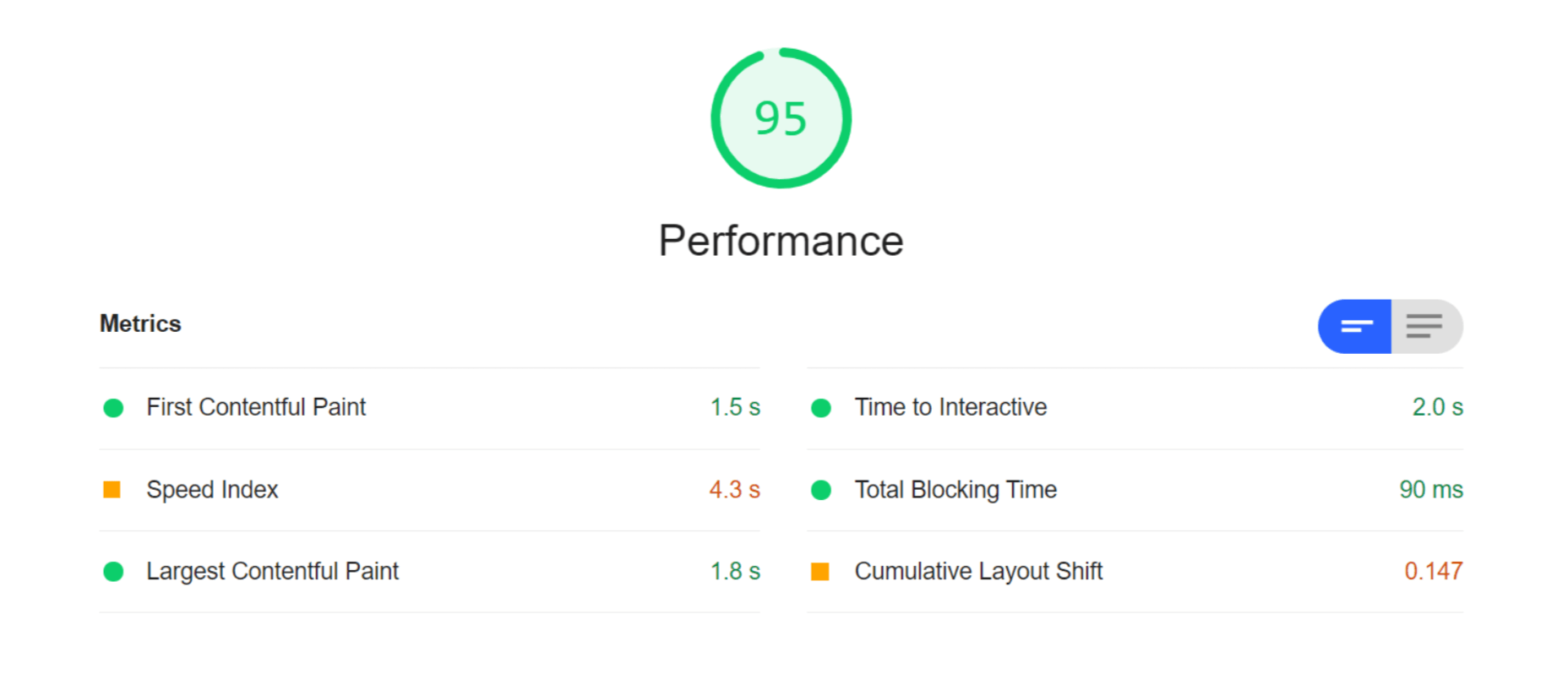

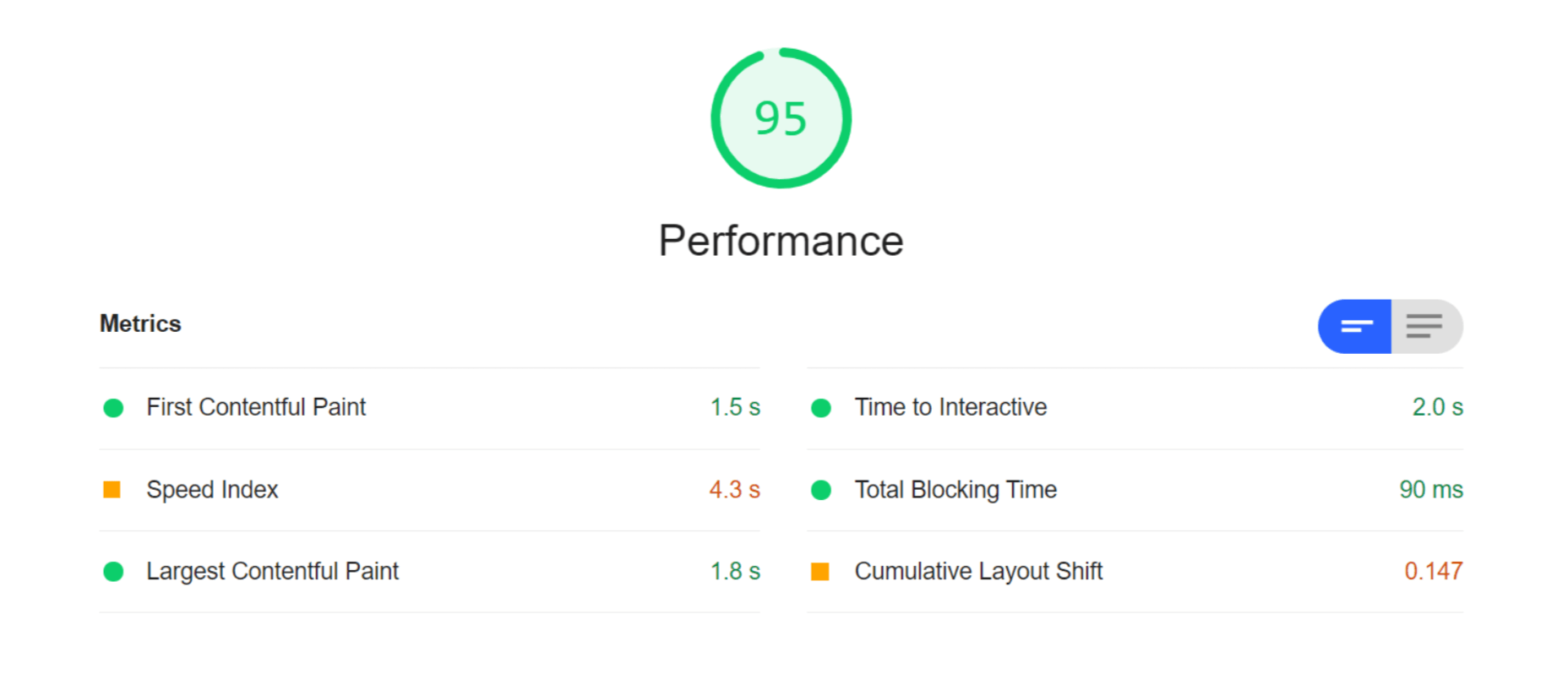

So, finally, let’s do another Lighthouse audit – this time using ImageEngine on top of Cloudinary. Here are the results:

With ImageEngine, I finally scored in the green with 95. All the metrics that have to do with the sheer speed at which image content loads improved. The Speed Index and LCP, which is the most important, improved dramatically. CLS scored worse, but this typically varies from test to test.

You can find another and more extensive breakdown of the performance and pricing comparison here.

Transformations, Bandwidth Utilization, and Cost

Cloudinary’s pricing plans work on a credit-based system. Starting with the free account, you get 25 credits/month. Each credit can be used for 1,000 transformations, 1 GB of storage, or 1 GB of net viewing bandwidth. The other two packages cost $99 for 225 credits and $249 for 600 credits, respectively.

You should plan to generate a minimum of 5 transformations per image. In effect, that limits you to around 200 images with the free plan, excluding whatever manual transformations you make.

ImageEngine’s Basic plan costs $49 and provides you with 100 GB of Smart Bytes. Smart Bytes are based on optimized image content and translate to roughly 400-500 GB of raw images.

So, with Cloudinary, you have to compromise between bandwidth and storage usage as well as the number of transformations you can make. Transformations for Cloudinary are counted as they are dynamically generated on-demand.

However, if you use ImageEngine for optimization, you can switch off Cloudinary’s auto-optimization. When a new image variant is needed, it will be generated and delivered via ImageEngine. Considering variant count isn’t limited by ImageEngine, this will drastically cut down on the number of credits you’ll need to spend on transformations.

Effectively, that means you could use the bulk of your Cloudinary credits purely for storage and specific transformations. For example, advanced cropping, applying effects, or color adjustments. These are, after all, the main functions of a DAM.

With this setup, ImageEngine’s Basic plan and Cloudinary’s free plan should be adequate for most websites, saving around $50 a month.

How to Implement Cloudinary with ImageEngine

Signing up for Both Services

As it will house all of your image assets, the logical place to start would be to sign up with Cloudinary.

Create a (free) account, and make sure to take note of your “cloud name” during the setup wizard. This will be the name of your designated storage location on the Cloudinary platform and is usually a garbled string like di2zgnxh0 by default. However, you can change this to something more meaningful.

Once you’ve signed up, you can start uploading your image assets and creating different versions/transformations of them. Setting up Cloudinary integration on a CMS, like WordPress, is usually straightforward. Just indicate the CMS you’ll be using, copy the API key, install the plugin, and activate it.

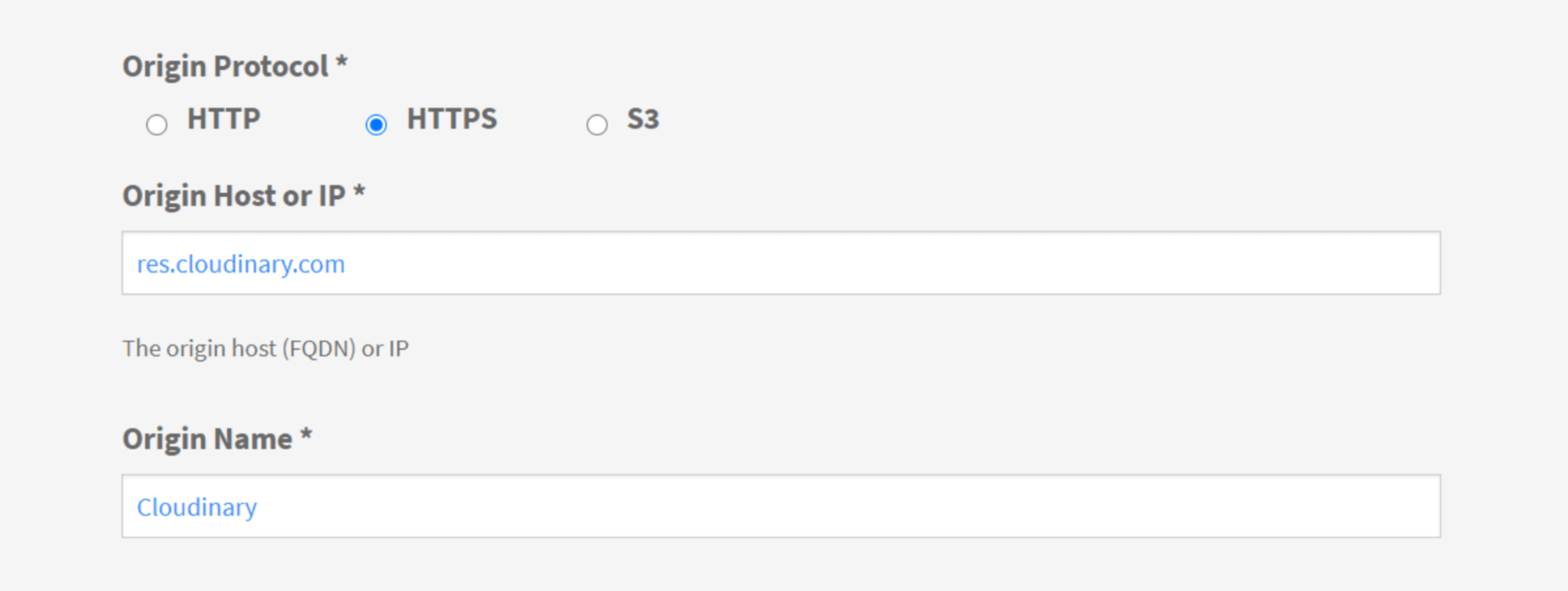

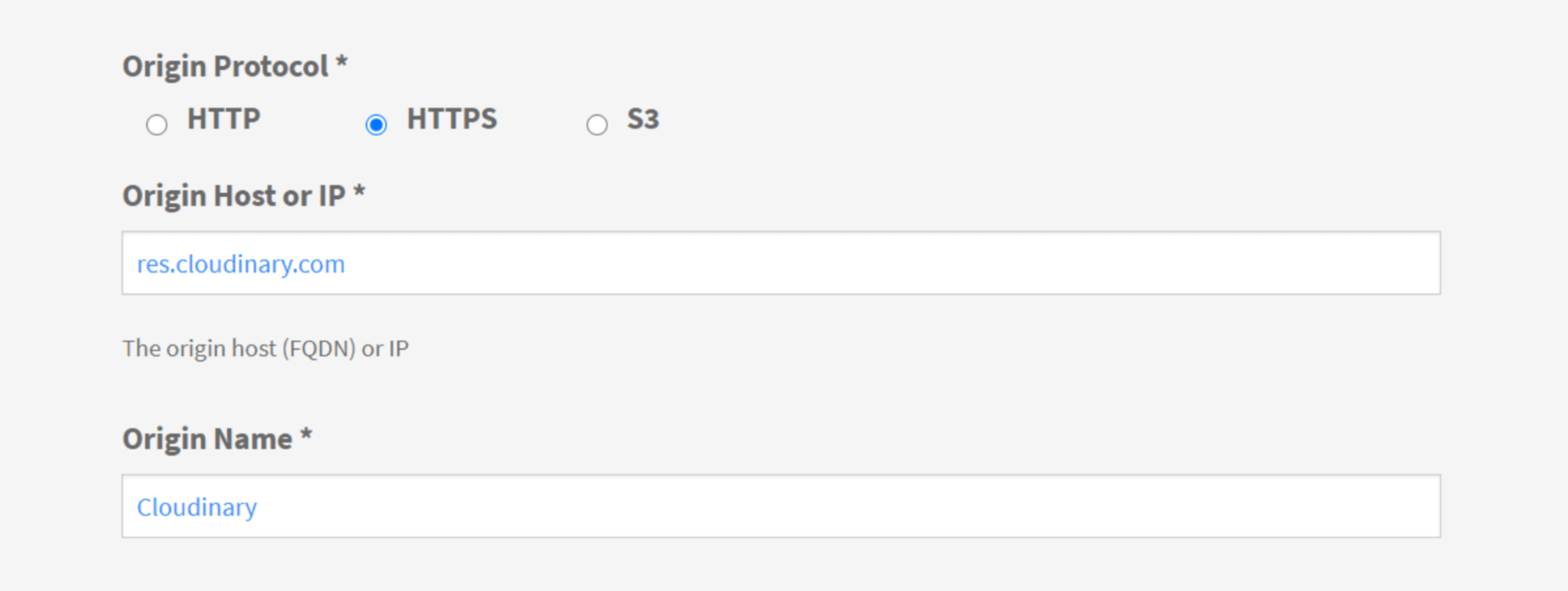

Next, sign up for a free trial with ImageEngine. There will also be a short setup wizard during which you will:

- Provide ImageEngine with the website where your images will be delivered.

- Supply your image origin (in this case, your Cloudinary web folder). For now, you can only add the Cloudinary, e.g., res.cloudinary.com.

- Get your ImageEngine image-serving domain, e.g., {randomstring}.cdn.imgeng.in

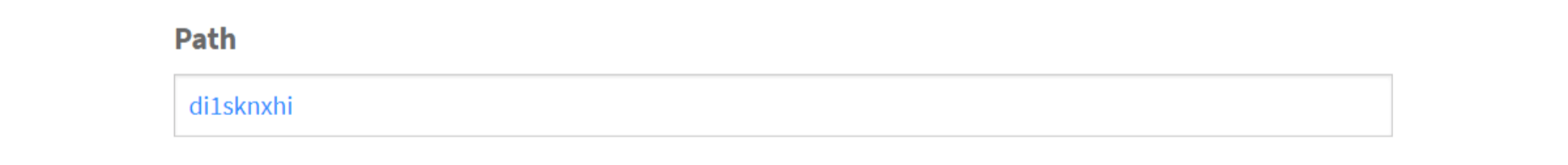

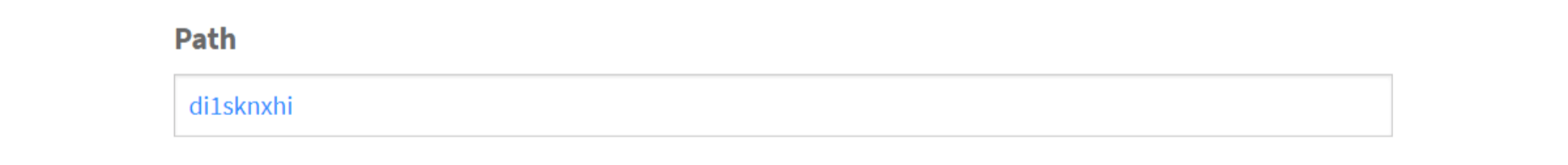

When in your ImageEngine dashboard, you’ll see this domain listed under “Engines” as well as an entry for Cloudinary under “Origins.” Edit the latter and under “Advanced,” add your Cloudinary folder to the “PATH” field.

That’s it, you should now be able to store and manage images via Cloudinary and serve them via the ImageEngine CDN.

Dynamically Loading Specific Image Variants

Let’s take a look at a use case for loading different transformations of individual images on your site. This example will showcase how you can use Cloudinary’s advanced image editing tools to transform images while still reaping the optimization rewards of using ImageEngine as your image CDN.

A popular practice today is to use rounded images for team, client, or profile portraits. Using Cloudinary, you can load this transformation using the following URL:

https://res.cloudinary.com/myimages/image/upload/w_400,h_400,c_crop,g_face,r_max/w_200/profile.jpg

This will resize the image to 400 by 400px, focus on the face, and apply the maximum amount of radial cropping around it – to a width of 200px.

The same image can then be accessed via your ImageEngine delivery engine simply by swapping out the domain:

https://images.myimageengine.com.imgeng.in/image/upload/w_400,h_400,c_crop,g_face,r_max/w_200/profile.jpg

NOTE: I added my Cloudinary folder designation (“myimages”) as the path to my image origin. With that config, I don’t need to include it every time I use the image URL.

For example, you can set up the origin like this:

And, then under advanced:

If I specifically wanted to load the profile picture in WebP format (for transparency support, for example), I could add the ImageEngine directive f_webp:

https://images.myimageengine.com.imgeng.in/image/upload/w_400,h_400,c_crop,g_face,r_max/w_200/?imgeng=/f_webp/profile.jpg

ImageEngine and Cloudinary – The Wrap Up

Both ImageEngine and Cloudinary are superb platforms that can make managing image and video assets easier and improve your website maintenance. However, both services have their specialty in which they outperform each other.

For ImageEngine, it’s delivering blisteringly fast image loading times in next-gen formats and with a minimal loss of visual quality.

For Cloudinary, it’s providing a visual interface to organize, store, and edit your image and video assets.

As a further incentive, letting each of these services handle what they’re best at can lead to lowering your long-term operating costs.

[– This is a sponsored post on behalf of ImageEngine –]

Source

The post Start Using a Smart DAM and Image Optimization Stack first appeared on Webdesigner Depot.

Source de l’article sur Webdesignerdepot

On June 29th,

On June 29th,

Asset management and website performance optimization are two of those unavoidable headaches faced by every website owner.

Asset management and website performance optimization are two of those unavoidable headaches faced by every website owner.

Everyday design fans submit incredible industry stories to our sister-site,

Everyday design fans submit incredible industry stories to our sister-site,